This dying world already learned about Pandora and Pegasus and more of such lawlessness/criminality of establishments (and did nothing).

The following enables an appreciation of the interconnectedness of [the common objectives of] various forms [and inner realities] of evil.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Gen Z workers are not tech-savvy in the workplace – and it’s a growing problem

It turns out Gen Zers have a common secret. They’re not as comfortable with new technology as older generations would typically presume.

Sure, they may have grown up with instant access to information and an affinity for digital devices that older generations had to learn. But that has led to a widespread presumption that Gen Zers are therefore innately good with tech. Now, new research is showing that may not be the case at all when it comes to workplace tech. In fact, this presumption from older generations is leading a larger number of young professionals to experience “tech shame,” according to HP’s “Hybrid Work: Are We There Yet?” report, published in late November.

One in 5 of the 18-to-29-year-olds polled in the report, which surveyed 10,000 office workers in 10 markets including the U.S. and U.K., said they felt judged when experiencing technical issues, compared to only one in 25 for those aged 40 years and over. Further, 25% of the former age group would actively avoid participating in a meeting if they thought their tech tools might cause disruption, whereas it was just 6% for the latter cohort.

“We were surprised to find out that young workers are feeling more ‘tech shame’ than their older colleagues, and this could be due to a number of issues,” said Debbie Irish, head of human resources in the U.K. and Ireland at HP. First, in a hybrid work scenario, more seasoned colleagues would likely have higher disposable incomes with which to buy better equipment for their homes, she suggested.

Additionally, those who had started their careers during or since the pandemic were probably low on confidence at work. “Some young professionals are entering the workforce for the first time in fully virtual settings,” said Irish. “They have less face-to-face time in the office than any other generation and have limited access to senior employees, mentors and even their bosses.”

https://www.allresearchjournal.com/archives/2016/vol2issue3/PartM/2-3-182.pdf

Fomo, stress and sleeplessness: are smartphones bad for students?

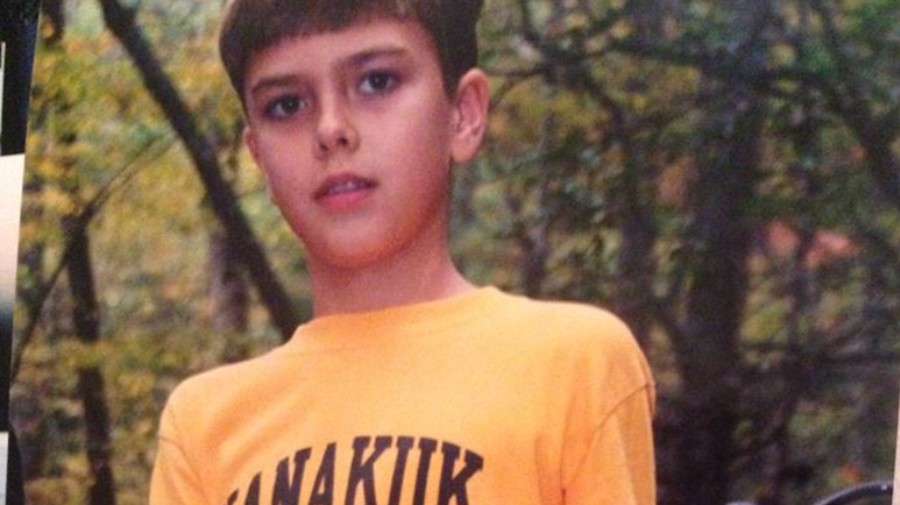

A Christian Camp Director Abused Dozens of Kids. Now, a Victim Says the Camp Lied to Coerce Him Into an NDA.

Logan Yandell started going to Kanakuk in Branson, Missouri when he was 7 years old. It was the summer of 2002 and he was excited—the Christian sports camp advertised the “best summer ever” and was popular with the older kids from his church.

Kanakuk wasn’t an obvious fit for his personality. A quiet, shy kid, he wasn’t particularly athletic and much preferred to play music. But he saw the camp as an extension of his church, which was important to him and his family. Kanakuk touts itself as a summer wonderland set against the backdrop of Christian teachings, and nearly half a million campers have passed through its gates since it was founded in 1926. Parents pay thousands of dollars a week for their kids to mix faith with outdoor adventures like canoeing, water slides, ziplines, archery, and more.

When Yandell arrived on the camp’s sprawling campus, he met Pete Newman almost immediately. A former counselor turned director, Newman was Kanakuk’s star, and seen as the disciple of Joe White, Kanakuk’s CEO and a high profile Evangelical speaker.

“I wanted to be like Pete when I grew up,” Yandell, now 27, told VICE News. “Pete was adored by so many people and families and respected from the camp; they elevated him so much. He was the camp’s poster-child.”

What happened next was devastating: Yandell would become one of dozens of boys victimized by Newman, who was ultimately convicted of child sexual abuse. Camp leaders were adamant they had no idea Newman posed a risk to kids. But years later, his victims and their families have accused the camp, according to previous court documents and a new lawsuit, of putting children in danger by ignoring repeated warnings about his inappropriate behavior. And a new lawsuit from one victim accuses the camp of covering up negligence by coercing victims into signing fraudulent non-disclosure agreements.

When Yandell returned the following year, Newman kept up their close relationship, singling him out from other campers so they could spend time one on one.

That first summer, Yandell didn’t know what lay ahead. He enjoyed his time at camp, and joined Newman’s Bible study group, which continued via long distance correspondence long after the summer ended. When Yandell returned the following year, Newman kept up their close relationship, singling him out from other campers so they could spend time one on one.

At first, the treatment was an honor. “Being close with Pete was seen as, ‘There’s something special about your kid when your kid is close to Pete,’” Yandell recalled.

Later that year, Yandell says Newman started to sexually abuse him. It began that fall on a trip to Newman’s home, just down the road from Kanakuk—a visit Yandell remembers as “kind of a birthday gift” as he’d just turned 9.

“Pete really treated it as a game,” he said, adding that Newman told him they could avoid the sin of lusting after women by masturbating with each other. “He would use scripture to his advantage and make it like we were doing something that was keeping us from sinning. At the time, I guess it made sense to me because of the indoctrination.”

Yandell didn’t tell anyone about the abuse for years.

He says he didn’t really understand what was happening to him. Newman was a revered leader at the camp and worked so closely with White, who had become a friend of Yandell’s family, that Yandell trusted him.

The abuse continued for 4 years, Yandell said, escalating until Newman raped him multiple times in 2008 when he was 13 years old.

After these assaults, he distanced himself from Newman and said he didn’t want to spend time with him anymore – though he still didn’t tell his family why. “I was confident that I was uncomfortable and that what was happening to me was not normal and that I was not ok with it,” Yandell said. “My parents were confused. They were like, ‘We thought you loved Pete.’”

He didn’t tell anyone what had happened until 2009, when news eventually broke that Newman was accused of abusing dozens of other children. Yandell finally shared with his family that he, too, had been a victim.

“He would use scripture to his advantage and make it like we were doing something that was keeping us from sinning. At the time, I guess it made sense to me because of the indoctrination.”

Newman was ultimately arrested, charged with and convicted of multiple counts of child sexual abuse; one judge determined his victims numbered “at least 57.” He is currently serving back to back life sentences in a Missouri state prison.

The camp claimed to have been blindsided, issuing a statement that they were “deeply saddened and shocked” by the news. For years, Kanakuk maintained that leadership had no prior knowledge that Newman was a danger to kids.

But over time, victims would come to believe that wasn’t exactly the case.

In the immediate aftermath of Newman’s arrest, Yandell’s father, Greg, said he confronted White: “I asked Joe point blank, ‘Did you ever see anything that concerned you about Pete Newman, or was Pete ever in a situation that was inappropriate with kids?’ Point blank, ‘No, Greg, we never saw anything that would cause any kind of concern and this comes as just a big of a surprise to us as it does to you.’”

The family ended up signing a settlement agreement with the camp in 2010, just a year after Yandell came forward, which, according to the lawsuit, includes non-disclosure language that restricts them from talking about how much they were paid.

“It was pretty clear that Joe wanted us to settle quickly,” Greg Yandell said. “When I read the language of the non-disclosure agreement, my mindset was, ‘This won’t matter anyway because they never saw anything with Pete, so there’s no reason to worry about having a non-disclosure agreement.’ That entire process was completely predicated on me accepting truth from Joe White.”

“I completely trusted Joe,” Greg Yandell told VICE News after the lawsuit was filed. “It just didn’t cross my mind at all that Joe could have been lying to me, or covered things up for years and years.”

In an affidavit to the lawsuit, he said the same thing. “We discovered that Kanakuk and White’s representations regarding prior knowledge of Newman’s sexual misconduct were false,” Greg Yandell stated. “We would not have agreed to the settlement agreement on behalf of our son but for the false and material misrepresentations made by Kanakuk and White regarding its knowledge of Newman’s sexual misconduct with young boys.”

In 2021, victims started going public on a website called FactsAboutKanakuk.com, sharing their stories with conservative publication The Dispatch, and in interviews with VICE News.

Victims accused Kanakuk of knowing that Newman was a danger and putting them at risk, and silencing them with non-disclosure agreements after their abuse. An unknown number of victims signed settlements with the camp, some of which contain non-disparagement or non-disclosure clauses. While Kanakuk claims to “absolutely support the right of victims to share their story in pursuit of their healing,” victims have told VICE News they were afraid if they spoke publicly, they would be accused of disparaging camp and face legal action, like what happened to the Alarcons, a family whose son was abused at camp.

The Alarcons refused to sign non-disparagement or confidentiality clauses in their settlement, and were later pursued by Kanakuk for violating the terms of their agreement—leading to legal proceedings they say cost them $40,000, VICE News reported last year.

Over the past two years, this growing tide of victims and their families have demanded that Kanakuk release all parties from any non-disclosure agreements and allow them to speak publicly without fear of retribution.

Victims accused Kanakuk of knowing that Newman was a danger and putting them at risk, and silencing them with non-disclosure agreements after their abuse.

In a statement on its website, the camp has acknowledged this movement: “We realize that the complex language of settlement agreements may have silenced some victims. We also realize that we have added confusion and frustration when we have spoken on this topic. We were wrong in our understanding of the language of many of these agreements, and we failed to recognize the restrictions – both real and perceived – that many victims are under.”

But now, Yandell is going a step further.

In a lawsuit filed last month in Missouri against Joe White, Kanakuk’s parent companies Kanakuk Heritage and Kanakuk Ministries, as well as the camp’s insurance provider, Yandell alleges his settlement agreement was fraudulent, as he never would have signed if White and Kanakuk leadership had told him and his family the truth about what they knew about Newman.

The suit argues that Kanakuk represented Newman’s abuse as “isolated” and that the “Defendants had no prior knowledge,” when in fact Kanakuk “actively concealed the reports of Newman’s sexual misconduct with minor children” and never took appropriate action.

It includes an affidavit from Will Cunningham, Newman’s direct supervisor from 1997 until 2005, in which he details multiple instances that camp leadership was aware of Newman inappropriately exposing himself to kids while at the camp. In 1999, for example, Newman was documented as having ridden a four-wheeler naked around campers, and in 2003 he swam and played basketball naked with young boys.

Cunningham attests that after these reports in 2003 he recommended Newman be terminated, but Newman was allowed to remain Assistant Director and was later promoted to Director of K-Kountry, Kanakuk’s camp for children ages 6 to 11.

In 1999, for example, Newman was documented as having ridden a four-wheeler naked around campers, and in 2003 he swam and played basketball naked with young boys.

The lawsuit includes several other examples of parents contacting the camp with concerns about Newman, like a mom in 2003 who called to report him for “unusual/sexual behavior” towards her son “after witnessing her son throw away his jeans” and “proclaiming ‘I never want to see Pete again.’” In 2006, another father contacted Kanakuk concerned by Newman’s contact with his son.

Yandell is seeking a jury trial and at least $25,000 in damages.

VICE News has previously reported that multiple parents complained about Newman’s behavior to the camp for years before he was ultimately arrested and charged with abuse, and that Kanakuk was aware of and documented his inappropriate activity, such as the “nightly hot tub ministries” he held with boys in 2006, according to documents obtained from a civil suit against Newman in 2011.

In one instance, a mother who called to report that her daughter had observed Newman touching a young male camper inappropriately told VICE News that a staffer dismissed the complaint, saying her daughter should re-evaluate her relationship with God and that she was not a good fit for Kanakuk.

Camp leadership did not report Newman to authorities, VICE News reported last year, but created what looks like a behavior plan that included spending more time with his wife and not having any more sleepovers with underage boys, according to the civil suit.

“If Joe had made the correct decision to fire Pete the very first time he abused kids, then my son would have never been abused, ever,” Greg Yandell said. “I want Joe White to admit that he’s lied to victims all these years and he’s lied to families all these years. If I had known all the facts, there is no possible way I would have ever settled with Kanakuk.”

“I’m not trying to destroy Kanakuk’s ministry, I’m just trying to get them to tell the truth,” Greg Yandell added. “Kanakuk continues to lie over and over about what they knew and when they knew.”

Despite the increased spotlight on the history of abuse and use of NDAs at Kanakuk, it remains a sought-after summer experience: The camp says more than 20,000 campers attend every year.

When reached for comment, a spokesperson for Kanakuk said simply, “Our policy is not to comment on pending litigation. We will respond further if or when appropriate. In the meantime, we continue to pray for all who have been affected by Pete Newman’s behavior.”

“I had given up complete hope on getting any justice around this,” Yandell said. “That NDA was very much debilitating for a very long time.”

Yandell’s could be the first of many such cases against Kanakuk that seek to void NDAs, opening the door for survivors to speak freely. Yandell’s lawyer Brian Kent told VICE News he has been in touch with “scores” of Kanakuk abuse survivors and “the goal is to get justice for as many people as possible.”

For Yandell, who struggled with anxiety, depression, substance abuse, and recurrent health issues for years following his abuse, the lawsuit represents a way forward. “I had given up complete hope on getting any justice around this,” he said. “That NDA was very much debilitating for a very long time.”

He said he was inspired to speak out by his fellow victims, such as Trey Carlock, a former camper and Newman victim who died by suicide in 2019, and whose obituary references his abuse at Kanakuk and the years he “fought valiantly against the trauma he suffered.”

“Trey Carlock no longer has his voice to speak out against these things,” Yandell said. “So for me it’s extremely important to use my voice to be able to speak the truth about what they continually cover up, even to this day.”

Facebook accused of continuing to surveil teens for ad targeting

The adtech giant formerly known as Facebook is still tracking teens for ad targeting on its social media platforms, according to new research by Fairplay, Global Action Plan and Reset Australia — apparently contradicting Facebook’s announcement this summer when the tech giant claimed it would be limiting how advertisers could reach kids.

Facebook has since rebranded the group business name to “Meta” — in what looks like a doomed bid to detoxify its brand following a never-ending string of scandals.

In the latest problem for Facebook/Meta, the adtech giant has been accused of not actually abandoning ad targeting for teens but, per the research, it has retained its algorithms’ abilities to track and target kids — continuing to maintain its AIs’ ability to surveil children so it can use data about what they do online to determine which ads they see in order to maximize engagement and boost its ad revenues.

So Facebook/Meta stands accused of failing to make a meaningful change to protect some of its most vulnerable users from hyper manipulative marketing — opting instead for a misleading ploy of stripping out a layer of targeting control from advertisers.

Although — in a response to the research — the tech giant denied it is using the tracking data it’s still linking to teens’ accounts to “personalize” ads to under 18s. It didn’t explain why it’s still collecting it, however.

An international coalition of public health and child development groups, human rights organizations and privacy campaigners has made the accusation, writing to Facebook/Meta flagging the findings of the research it commissioned and calling for the tech giant to come clean on how teens are really targeted on its platforms — and actually commit to ending the practice — accusing it in the open letter of misleading both the public and lawmakers.

The researchers found evidence that advertising on Facebook’s platforms continues to be “optimized” for teens by algorithms; and that Facebook/Meta is using surreptitiously harvested information (such as from tracking pixels) about children’s online behaviour to feed its AI-driven ad targeting in order to keep lining its pockets.

Yet back in July — when Facebook/Meta announced (global) changes to advertisers’ ability to target under 18s (on Instagram, Facebook and Messenger) — the tech giant implied targeting would be limited to just age, gender and location, writing then that it would “only allow advertisers to target ads to people under 18 (or older in certain countries) based on their age, gender and location”; and specifying that it was removing previously available targeting options (such as “those based on interests or activity on other apps and websites”).

“[W]hile Facebook says it will no longer allow advertisers to selectively target teenagers, it appears Facebook itself continues to target teens, only now with the power of AI,” the coalition of advocacy groups writes in the letter. “Replacing ‘targeting selected by advertisers’ with ‘optimisation selected by a machine learning delivery system’ does not represent a demonstrable improvement for children, despite Facebook’s claims in July.

“Facebook is still using the vast amount of data it collects about young people in order to determine which children are most likely to be vulnerable to a given ad. This practice is especially concerning, given ‘optimisation’ might mean weight loss ads served to teens with emerging eating disorders or an ad being served when, for instance, a teen’s mood suggests they are particularly vulnerable.”

They go on to warn that if the research findings are correct, “advertising for children is in reality even more personalised on Facebook, Instagram and Messenger.”

The letter comes at an exceptionally awkward time for Facebook/Meta after whistleblower Frances Haugen leaked thousands of pages of internal documents to the press — leading to high profile reporting flagging internal discussions of Instagram’s toxicity for teens, among other excoriating issues.

Haugen has since spent hours giving in person evidence to lawmakers on both sides of the Atlantic — including to the European Parliament where the EU is in the process of finalizing two packages of sweeping digital regulation that will dial up transparency and governance requirements on platforms such as Facebook and Instagram; and apply ex ante rules to the biggest tech giants like Meta.

In recent months, a number of MEPs have been pushing to amend the EU’s draft legislation to include an outright ban on surveillance advertising — in favor of privacy-safe alternatives like contextual ads. And the coalition’s letter and research looks likely to build further support for such a move.

The international coalition denouncing Facebook’s “misleading” double-dealing is also calling for a partial end to “creepy surveillance ads” — at least for advertising that’s targeted at young people.

Signatories to the letter include a wide range of civil society advocacy groups, from Amnesty International USA to Fair Vote, UK, Friends of the Earth, Center for Digital Democracy, National Center on Sexual Exploitation, Parent Coalition for Student Privacy, Privacy International, Stop Predatory Gambling and the Campaign for Gambling-Free Kids, Tech Transparency Project and many more.

In the letter, they write that their suspicions over Facebook’s ongoing ad targeting of teens were raised by evidence given by Haugen — citing testimony last month, in front of the U.S. Senate, when she said: “I’m very suspicious that personalised ads are still not being delivered to teenagers on Instagram, because the algorithms learn correlations. They learn interactions where your party ad may still go to kids interested in partying, because Facebook almost certainly has a ranking model in the background that says this person wants more party-related content.”

For the report, the researchers analyzed whether Facebook continues to track children’s browsing data and other online activity for ad purposes — looking at Conversion APIs, such as Facebook Pixel and app SPK (which their report notes are “used exclusively to gather information for advertising purposes”) — and finding Facebook was collecting Facebook Pixel26 data from accounts registered to children.

Their method involved the creation of three experimental Facebook accounts — on “clean browsers” — with one registered with the age of a 13 year old and the other two for 16 year olds.

“Our test account browsed a number of webpages containing an embedded Facebook Pixel. As the test account was logged in to Facebook, data about these visits could be identified by Facebook Pixel because of the login Cookie ‘c_user,’” they write.

“Using this Facebook Pixel data, Facebook can collect data from other browser tabs and pages that children open, and harvest information like which buttons they click on, which terms they search or products they purchase or put in their basket (‘conversions’) … There is no reason to store this sort of conversion data, except to fuel the ad delivery system.”

“This demonstrates that Facebook’s ad delivery system is still harvesting children and teenagers data,” the researchers conclude, going on to argue that Facebook/Meta removing advertisers’ ability to target kids but maintaining tracking so its AI can infer correlations for targeting does not represent any kind of improvement — nor the claimed “precautionary approach” Facebook/Meta claimed it would be taking this summer — and suggesting it may in fact be worse (not least because targeting of teens is entirely obfuscated).

“Facebook’s ad delivery system continues to harvest teens’ data for the sole purpose of serving them surveillance advertising, with all the associated concerns,” they add. “Replacing ‘targeting selected by advertisers’ with ‘targeting optimised by AI’ does not represent a demonstrable improvement for children in the way that Facebook characterised this in both their initial announcement and [Facebook’s global head of Safety Ms Antigone] Davis’ Senate testimony. It is, in all likelihood, worse.”

In the letter, the coalition points out that Facebook/Meta has itself acknowledged the harms of surveillance advertising for kids — hence taking the step of limiting how advertisers can reach children.

However if it has not actually stopped tracking and targeting kids with ads then there is no meaningful change — and this summer’s gesture looks like (yet) more misleading marketing from the company’s 24/7 crisis PR department.

Facebook/Meta was contacted for comment on the research and the coalition’s letter.

A spokesperson sent this statement — denying that the tracking data the coalition found being associated with teens’ accounts is used for targeting teens with ads, even though Facebook/Meta has still received it, stored it and linked it to the user — claiming:

“It’s wrong to say that because we show data in our transparency tools it’s automatically used for ads. We don’t use data from our advertisers’ and partners’ websites and apps to personalize ads to people under 18. The reason this information shows up in our transparency tools is because teens visit sites or apps that use our business tools. We want to provide transparency into the data we receive, even if it’s not used for ads personalization.”

In her evidence to lawmakers in recent weeks, Haugen has repeatedly suggested there may be no such thing as safe ‘AI-driven’ social media for young teens, given pressures faced by children whose brains are still developing — warning that Facebook’s algorithms are profiting by exploiting the mental health of vulnerable teens.

In a section of the Fairplay report on surveillance advertising and children, the researchers also warn that surveillance advertising intensifies the manipulation of children through what they describe as “a huge asymmetry of ability and information.”

They go on to cite what they describe as “emerging evidence” that children and young people resent being targeted by surveillance advertising — pointing to a recent Australian poll finding that 82% of 16 and 17 year olds have “come across ads that are so targeted they felt uncomfortable.”

The report also notes other findings, such as that a majority (65%) of Australian parents reported being “uncomfortable” with businesses targeting ads to children based on info they have obtained by tracking a child online; and an overwhelming majority (88%) of U.S. parents believe “the practice of tracking and targeting kids and teens with ads based on their behavioral profiles” should be prohibited.”

With an excoriating global glare of attention on the workings of its ad tools, Facebook announced another change earlier this month — saying it would no longer allow advertisers to target political beliefs, religion and sexual orientation.

However it did not say it would stop tracking users’ online activity and feeding that data to its ad-targeting algorithms — meaning its AIs will be able to identify proxies that can be used to carry on that kind of sensitive targeting, just in a less transparent fashion. Facebook was also very keen to reassure advertisers that they could still use alternative tools it offers for granular targeting of users — such as engagement custom audiences and lookalike audiences.

So Meta’s internal “reforms” look intended to maintain its ad empire’s intrusive (and lucrative) targeting capabilities — while shielding its business from accusations of exploitation, manipulation and intrinsic data-fuelled harm.

(Tokyo) – Governments of 49 of the world’s most populous countries harmed children’s rights by endorsing online learning products during Covid-19 school closures without adequately protecting children’s privacy, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. The report was released simultaneously with publications by media organizations around the world that had early access to the Human Rights Watch findings and engaged in an independent collaborative investigation.

“‘How Dare They Peep into My Private Life?’: Children’s Rights Violations by Governments that Endorsed Online Learning during the Covid-19 Pandemic,” is grounded in technical and policy analysis conducted by Human Rights Watch on 164 education technology (EdTech) products endorsed by 49 countries. It includes an examination of 290 companies found to have collected, processed, or received children’s data since March 2021, and calls on governments to adopt modern child data protection laws to protect children online.

“Children should be safe in school, whether that’s in person or online,” said Hye Jung Han, children’s rights and technology researcher and advocate at Human Rights Watch. “By failing to ensure that their recommended online learning products protected children and their data, governments flung open the door for companies to surveil children online, outside school hours, and deep into their private lives.”

Of the 164 EdTech products reviewed, 146 (89 percent) appeared to engage in data practices that risked or infringed on children’s rights. These products monitored or had the capacity to monitor children, in most cases secretly and without the consent of children or their parents, in many cases harvesting personal data such as who they are, where they are, what they do in the classroom, who their family and friends are, and what kind of device their families could afford for them to use.

Most online learning platforms examined installed tracking technologies that trailed children outside of their virtual classrooms and across the internet, over time. Some invisibly tagged and fingerprinted children in ways that were impossible to avoid or erase – even if children, their parents, and teachers had been aware and had the desire to do so – without destroying the device.

Most online learning platforms sent or granted access to children’s data to advertising technology (AdTech) companies. In doing so, some EdTech products targeted children with behavioral advertising. By using children’s data – extracted from educational settings – to target them with personalized content and advertisements that follow them across the internet, these companies not only distorted children’s online experiences, but also risked influencing their opinions and beliefs at a time in their lives when they are at high risk of manipulative interference. Many more EdTech products sent children’s data to AdTech companies that specialize in behavioral advertising or whose algorithms determine what children see online.

With the exception of Morocco, all governments reviewed in this report endorsed at least one EdTech product that risked or undermined children’s rights. Most EdTech products were offered to governments at no direct financial cost. By endorsing and enabling the wide adoption of EdTech products, governments offloaded the true costs of providing online education onto children, who were unknowingly forced to pay for their learning with their rights to privacy and access to information, and potentially their freedom of thought.

Few governments checked whether the EdTech they rapidly endorsed or procured for schools were safe for children to use. As a result, children whose families could afford to access the internet, or who made hard sacrifices to do so, were exposed to the privacy practices of the EdTech products they were told or required to use during Covid-19 school closures.

Many governments put at risk or violated children’s rights directly. Of the 42 governments that provided online education to children by building and offering their own EdTech products for use during the pandemic, 39 governments made products that handled children’s personal data in ways that risked or infringed on their rights. Some governments made it compulsory for students and teachers to use their EdTech product, subjecting them to the risks of misuse or exploitation of their data, and making it impossible for children to protect themselves by opting for alternatives to access their education.

Children, parents, and teachers were largely kept in the dark about these data surveillance practices. Human Rights Watch found that the data surveillance took place in virtual classrooms and educational settings where children could not reasonably object to such surveillance. Most EdTech companies did not allow students to decline to be tracked; most of this monitoring happened secretly, without the child’s knowledge or consent. In most instances, it was impossible for children to opt out of such surveillance and data collection without opting out of compulsory education and giving up on formal learning during the pandemic.

Human Rights Watch conducted its technical analysis of the products between March and August 2021, and subsequently verified its findings as detailed in the report. Each analysis essentially took a snapshot of the prevalence and frequency of tracking technologies embedded in each product on a given date in that window. That prevalence and frequency may fluctuate over time based on multiple factors, meaning that an analysis conducted on later dates might observe variations in the behavior of the products.

It is not possible for Human Rights Watch to reach definitive conclusions as to the companies’ motivations in engaging in these actions, beyond reporting on what it observed in the data and the companies’ and governments’ own statements. Human Rights Watch shared its findings with the 95 EdTech companies, 196 AdTech companies, and 49 governments covered in this report, giving them the opportunity to respond and provide comments and clarifications. In all, 48 EdTech companies, 78 AdTech companies, and 10 governments responded as of May 24, 12 p.m. EDT. Several EdTech companies denied collecting children’s data. Some companies denied that their products were intended for children’s use. AdTech companies denied knowledge that the data was being sent to them, indicating that in any case it was their clients’ responsibility not to send them children’s data. These and other comments are reflected and addressed in the report, as relevant.

As more children spend increasing amounts of their childhood online, their reliance on the connected world and digital services that enable their education will likely continue long after the end of the pandemic. Governments should pass and enforce modern child data protection laws that provide safeguards around the collection, processing, and use of children’s data. Companies should immediately stop collecting, processing, and sharing children’s data in ways that risk or infringe on their rights.

Human Rights Watch has launched a global campaign, #StudentsNotProducts, which brings together parents, teachers, children, and allies to support this call and demand protections for children online.

“Children shouldn’t be compelled to give up their privacy and other rights in order to learn,” Han said. “Governments should urgently adopt and enforce modern child data protection laws to stop the surveillance of children by actors who don’t have children’s best interests at heart.”

International Media Consortium

EdTech Exposed is an independent collaborative investigation that had early access to Human Rights Watch’s report, data, and technical evidence on apparent violations of children’s rights by governments that endorsed education technologies during the Covid-19 pandemic. The consortium provided weeks of independent reporting by more than 25 investigative journalists from 13 media organizations in 16 countries. It was coordinated by The Signals Network, an international nonprofit organization that supports whistleblowers and helps coordinate international media investigations that speak out against corporate misconduct and human rights abuses. Human Rights Watch provided financial support to Signals to establish the consortium, but the consortium is independent from and operates independently from Human Rights Watch.

The media organizations involved include ABC (Australia), Chosun Ilbo (Republic of Korea), El Mundo (Spain), Folha de São Paulo (Brazil), The Globe and Mail (Canada), Kyodo News (Japan), McClatchy/Miami Herald/Sacramento Bee/Fort Worth Star-Telegram (USA), Mediapart (France), Narasi TV (Indonesia), OCCRP (Cameroon, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, and Zambia), The Daily Telegraph (UK), The Wire (India), and The Washington Post (USA).

In the coming weeks, Human Rights Watch will release its data and technical evidence, to invite experts, journalists, policymakers, and readers to recreate, test, and engage with its findings and research methods.

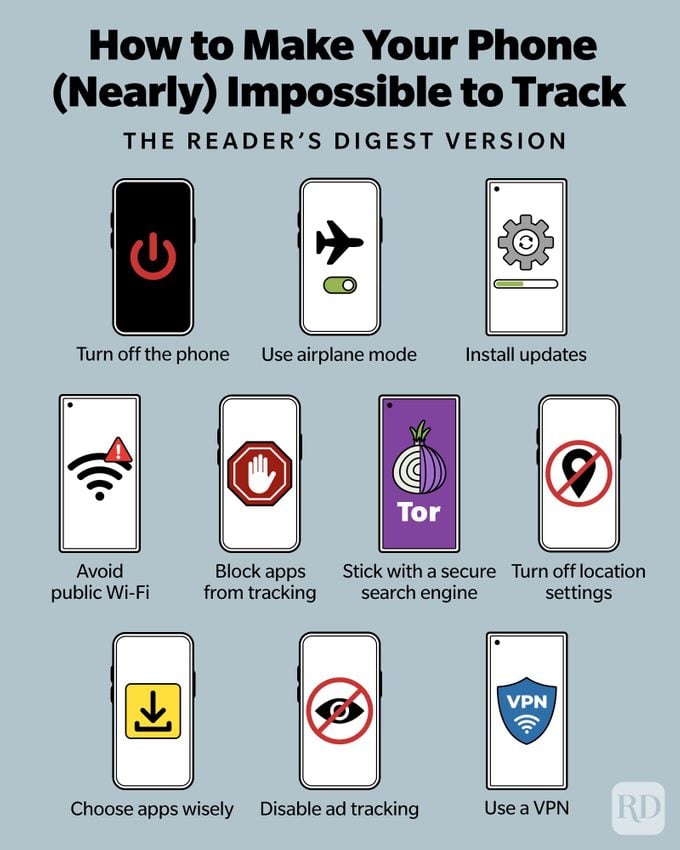

How to Make Your Phone (Nearly) Impossible to Track—and Keep Personal Information Safe

The more we use our phones, the more personal information we give up. So how do you make your phone impossible to track and keep your online data secure? We asked tech experts for their top tips.

Let’s face it: At best, most of us are reliant on our phones these days. (At worst, we’re downright addicted.) But do you ever consider the things your smartphone knows about you? You may know how to tell if your computer has been hacked and what hackers can do with your cell phone number, but are you clued in to common smartphone security threats and data-tracking measures? Knowing the risks may have you wondering how to make your phone impossible to track.

See, even the most secure phones track users in a number of different ways, including through Bluetooth, Wi-Fi and GPS. You may think that if you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to worry about. But in today’s data-driven economy, your info is worth a lot. And there are good reasons you may want to avoid tracking. Perhaps you don’t want people making money off your data, you’re worried it might fall into the wrong hands or you just don’t like the idea of being snooped on.

“Location technology in cell phones could be helpful when looking for the nearest gas station, but it can also enable others to retrieve information about your whereabouts, legally or illegally,” Stephanie Benoit Kurtz, lead faculty for the College of Information Systems and Technology at the University of Phoenix, told Reader’s Digest. “Users rarely read the fine print associated with what is being tracked, and shared in that tiny print might be some very disturbing trends—everything from tracking the location of your device at all times to sharing information from your device, such as other applications installed, contacts, text messages and emails.”

If this concerns you too, look for signs someone’s tracking your cell phone, brush up on online security secrets and read on for some tips on how to make your phone impossible to track.

Smartphone tracking

You may think of the people tracking your smartphone as shadowy figures looking to steal your identity, your money or both. But there’s a whole range of people and organizations that track smartphones, not just hackers.

Smartphone tracking can be either active or passive. And no, those good passwords you’ve been using won’t make a difference. Active tracking, which uses GSM, 3G or 4G, is sometimes called a man-in-the-middle attack. This is illegal in most countries but may be employed by law enforcement and government security agencies investigating a specific threat.

Passive tracking uses Bluetooth beacons, Wi-Fi and GPS to approximate a user’s position. Various applications on your phone employ these methods. With some, that’s the whole point. Consider location-tracking apps and services that help parents keep a tab on their kids. Others harvest your data for their own business development and marketing purposes or sell it to the highest bidder.

Advertisers might use your data to show you targeted ads. Even the government buys location data, a fact that the Wall Street Journal reported in 2020. The Department of Homeland Security purchased data pulled from smartphones, and the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) used it to track undocumented immigrants.

How to make your phone impossible to track

While the government and law enforcement will probably always be able to track your phone if they really want to (more on that below), there are ways to reduce mobile security threats, delete your digital footprint, avoid spyware and make your phone impossible to track by apps. Let’s take a look.

Shut down the phone

Contrary to popular belief, there’s such a thing as iPhone spyware, even if you have the best iPhone security. The easiest and most complete way to stop your phone from being tracked is to shut it down completely.

“If you are this concerned about your activity being tracked/recorded, simply remove the means by which companies can do so, and your device will be its own isolated ecosystem,” says Brandon Wilkes, marketing manager of The Big Phone Store.

Obviously, this comes with the very real inconvenience of not being able to use your phone at all, and it’s probably not a practical solution for most people. Still want to use this method? Back up your phone on a computer before taking the plunge so you can still access the data.

Turn on airplane mode

Airplane mode isn’t just for flying the friendly skies. It’s also a handy quick fix if you want to stop the passive tracking of your phone. Of course, turning on airplane mode means you won’t be able to make calls or use the internet with your device.

“The easiest way to keep your phone from being tracked is to change a few settings,” says Baruch Labunski, CEO of digital marketing company Rank Secure. “The fastest and best way to do this is to turn on the airplane mode option. This shuts off cell and Wi-Fi radios installed inside your phone so it can’t connect to networks.”

Want to give it a go? Navigate to “Settings” and toggle on “Airplane Mode” to activate it on an iPhone or Android phone.

Turn off location settings

Turning off the location-based features of your phone can prevent GPS tracking. Switching to airplane mode will do this for you, but you can also turn off GPS tracking as an isolated feature on many devices, allowing you to still use your phone to make calls and access the internet.

“Google, Apple and Samsung all store and record your movements through the GPS functions of your phone,” says Nick Donarski, co-founder and chief technology officer of computer support services and blockchain firm ORE System.

Turn off location settings on iPhones or iPads:

- Go to “Settings.”

- Select “Privacy.”

- Tap “Location Services.”

- Toggle “Location Services” to the “off” position.

Turn off location settings on Android:

- Open the “App Drawer.”

- Go to “Settings.”

- Select “Location.”

- Enter “Google Location Settings.”

- Turn off “Location Reporting” and “Location History.”

- You can also select “Delete Location History” to remove all previous tracking data.

Turning off location settings will remove some of the functionality of certain apps and online services. With it disabled, for instance, map apps won’t be able to give you directions from here to there, and apps like Yelp can’t pull up restaurants in your vicinity. But if you’re really serious about not being tracked, you’ll need to return to old-school navigation methods, such as paper maps.

Use a VPN

A virtual private network (VPN) is a great way to enhance the security of your phone. “Connecting to a VPN changes your IP address [a string of characters that identifies each device browsing the internet] through the establishment of a private network, which prevents your location [and your browsing traffic] from being accurately determined and linked back to you,” says Labunski.

It’s worth noting, however, that VPNs and other security apps do not stop your phone from being tracked when it’s offline, so you’ll still have to use one of the methods above if you’re really concerned about passive location tracking.

Use a secure search engine

Have you ever considered what Google knows about you and what all those website cookies are up to? Certain lesser-known browsers act in a similar way to VPNs, allowing for anonymous searching without tracking.

Try downloading and using Onion Browser for iOS and Tor for Android. “[These browsers] can increase the user’s privacy and prevent tracking from outside parties by encrypting your information and relaying it through servers that mask your IP address,” says Wilkes. “They also feature plug-ins that prevent web pages from using Javascript, which can track user activity.”

If you’re hell-bent on dropping off the radar, you may also want to delete yourself from Google search.

Keep a close eye on app permissions

![]()

Every app you download to your phone should ask for permission for its tracking activities from the outset. If you don’t want a certain app to track you, deny these permissions straight away.

If you have an iPhone, you can also view app permissions by accessing your privacy report. Go to “Settings,” “Privacy” and then (at the bottom) “App Privacy Report.” You’ll need to tap “Turn On App Privacy Report” to see how your apps use your data.

The service allows users to “monitor when their location is being tracked, as well as when apps can use body sensors or view your contacts, messages, calls and calendar,” says Wilkes. “It is at the discretion of the user to decide if an app is trustworthy enough to access this data.”

Luckily, if you don’t want a specific app (or any app) to track your data, you can prevent it in a few simple steps.

Block apps from tracking on an iPhone:

- Go to “Settings.”

- Tap “Privacy.”

- Tap “Tracking.”

- Toggle off “Allow Apps to Request to Track” to stop all apps from tracking you.

Heads up: You can also give or revoke tracking access to specific apps by toggling the switch next to the app in the list below the “Allow Apps to Request to Track” field.

Block apps from tracking on an Android device:

- Go to “Settings.”

- Select “Locations.”

- Tap “App Locations Permissions.”

- Select the apps individually and change permissions to “Allow all the time,” “Only when using the app,” “Ask every time” or “Don’t allow.”

Why bother? “Every app, software and tech that installs and integrates into your mobile devices has intimate access to our personal lives, our whereabouts and even our personal activities through our images,” says Donarski. “The real answer to protecting ourselves is weaning ourselves off technology. But as that is not necessarily going to happen anytime soon, vigilance, education and extra scrutiny over the apps, messages and links we visit on our mobile devices are the key elements of securing yourself and your data.”

Install updates

Always install the latest operating system for your phone and the latest version of any apps you have. Updates often come with bug fixes and smartphone security improvements that protect your data better, especially if you select the right privacy options.

Be picky about what you install

Just because an app is free doesn’t mean it’s not costing you. Free apps make their money by showing you ads and/or selling your data to third parties like data brokers. Use the web version instead of the mobile version when possible, and always look carefully at the fine print before you install something on your phone.

“Prior to installing an app, you should understand exactly what the app is doing, what information the app is gathering and what information is being shared with that organization or third parties,” says Benoit Kurtz. “The Acceptable Use Agreement, or End User Agreement, matters. That tiny print covers things like information around the collection of location data, how it is collected and then what is done with that information.”

Disable ad tracking and personalization

![]()

Ad tracking makes it possible for companies to deliver personalized ads that are more appealing to you—and more likely to result in sales for the company. But this requires companies to collect data about you, such as your browsing and shopping habits and your physical location. Disabling cross-site tracking in your browser will minimize this intrusion.

If you have an iPhone, go to “Settings,” then scroll down to find your web browser of choice. Tap the browser name, then scroll down to the “Prevent Cross-Site Tracking” field. Toggle this to the “on” position to stop cross-site tracking on that browser.

On an Android device, you can prevent the Chrome browser from collecting or tracking your data by taking a few steps: In the app, tap the three dots to the right of the address bar, then tap “Settings.” Select “Privacy and Security” and then “Do Not Track.” Turn this off to stop ad tracking.

To further limit tracking, adjust Apple or Android advertising settings.

On an iPhone, go to “Settings,” “Privacy” and “Apple Advertising,” then toggle off “Personalized Ads.” If this feature is enabled on your Android device, go to “Settings,” “Privacy” and “Delete Advertising ID.”

Avoid public Wi-Fi

Public Wi-Fi networks, such as those in cafes and at airports, aren’t very secure and are more prone to malware attacks, snooping and rogue network interceptions. They also collect personal data from you, such as your name, date of birth and email address, before you can use the service. The more personal information you give, the more of your data is out there.

Campaign for better protection

As you’ve seen, there are several ways to make your phone impossible to track, but all involve some kind of sacrifice in functionality. The people who really hold the power here are those who run the telecom companies.

We should all be active in pushing these companies to provide better consumer protection, says Grant Gibson, executive vice president at CIBR Ready. “They are the real key to help solve this challenge,” he says. “We should all be involved and motivated to solve these challenges by using every channel possible to protect ourselves.”

It may seem like you have little sway here, but you can let lawmakers know that data privacy is a top concern, and you can vote for officials who support legislation to protect consumers’ data.

Frequently asked questions

TL;DR? Here are some quick reference points for the most frequently asked questions about smartphone security.

How would I know if my phone is being tracked?

There are a number of telltale signs that can tip you off to the fact that someone is tracking your phone or your phone has been hacked. These include:

- Your phone is hot. A phone that’s overheating when not in use may be running spyware in the background. The spyware makes your phone work harder and therefore produce more heat.

- Your battery drains quickly. You can blame spyware again. Remember, these programs make your phone work harder, which is why a tracked phone may constantly have low battery life.

- Your data usage shoots up. A tracked phone is constantly sending data to the hacker, so you may see your monthly usage shoot up for no good reason.

- Your phone reboots unexpectedly. Malware may interfere with your phone’s normal functioning, causing it to glitch and restart at random times.

- Your phone takes longer to shut down. If your phone is taking longer than usual to shut down, that may be because it’s trying to close tracking apps that are running in the background.

Can cell phones be tracked when turned off?

A cell phone that’s not connected to the internet can still be tracked via its GPS system, but a mobile phone that’s completely switched off is much more difficult to trace. You can, however, track a powered-down phone to the last location it was turned on via functions such as Apple’s Find My feature or by calling the service provider.

Law enforcement can also trace a turned-off phone via its International Mobile Equipment Identity (IMEI) number, a unique 15-digit code that can identify a device on a mobile network. With this number and the help of your mobile operator, officers can track your phone’s exact location, even when it’s off.

Your phone can also be effectively disabled, as carriers can deny services to a phone with an IMEI listed as stolen, even if it has a new SIM card. There’s really no way to hide or change your IMEI number—it’s inscribed into the metal SIM tray of every phone.

Can cell phones be tracked with location services turned off?

In short, yes. While turning off location services makes it much harder for people to track your phone, they can still glean its general whereabouts through your IP address, Wi-Fi and Bluetooth signals. Turning your phone off completely is the only way to prevent all tracking—unless someone has your IMEI, of course!

The bottom line: You can attempt to learn how to make your phone impossible to track, but all mobile phones can be tracked to a certain extent. The good news is that the above steps make it a whole lot harder.

Sources:

- Stephanie Benoit Kurtz, lead faculty for the College of Information Systems and Technology at the University of Phoenix

- Baruch Labunski, CEO of Rank Secure

- Nick Donarski, co-founder and chief technology officer of ORE System

- Brandon Wilkes, marketing manager of The Big Phone Store

- Grant Gibson, executive vice president at CIBR Ready

- Wall Street Journal: “Federal Agencies Use Cellphone Location Data for Immigration Enforcement”

- Apple: “Control app tracking permissions on iPhone”

- Google: “Turn ‘Do Not Track’ on or off”

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

New Project Aims to Map Cellular Variation in the Healthy Human Brain

Summary: Researchers aim to create a new brain atlas of variation in human brain cells.

Source: Broad Institute

People vary widely in how we think and behave and in our vulnerability to disease, and that variation can be traced at least in part to our brains. Yet scientists don’t know how healthy brains vary from one individual to the next, how genes and the environment generate that variation, or how human brains vary at the cellular and molecular levels.

To help answer these questions, researchers at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard are working to create an “atlas” of variation in human brain cells.

The project will include data from tens of millions of cells, collected by biobanks such as the NIH NeuroBioBank, from more than 200 people of diverse ages and genders.

The effort will serve as a valuable point of comparison for studies of brain disorders and is supported by the BRAIN Initiative at the National Institutes of Health, which aims to identify and characterize different cell types across the human brain.

To construct the atlas, the team plans to use techniques such as single-nucleus RNA-sequencing, which probes gene expression in individual cells, and single-nucleus ATAC-seq, which provides scientists with information about the accessibility of DNA for gene regulation. The scientists will also apply spatial transcriptomics to understand the spatial arrangement of cells and how gene expression varies across different regions of brain tissue.

The project is led by Evan Macosko, an institute member at the Broad and an attending psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital, and Steven McCarroll, an institute member and director of genomic neurobiology at the Broad’s Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research, and a professor of biomedical science and genetics at Harvard Medical School.

Other collaborators include core institute member Fei Chen, institute members Elise Robinson and Paola Arlotta, Mehrtash Babadi, associate director of machine learning, and Randy Buckner, an investigator at Mass General.

We spoke with Macosko and McCarroll about the tools they’ll use to probe this variation and what they hope their efforts will reveal about the brain in the following Q&A.

How did the idea for this atlas come about?

EM: Many years ago, when I was a postdoc with Steve, we wanted to develop a technology that would allow us to look systematically at gene expression in cells of the brain. We’d just seen the first hints of genetic signals associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. A big question was understanding how those genes are acting in specific brain cell types.

So we developed this technology called Drop-seq, which was the first tool for high-throughput single cell analysis. That paved the way for a lot of the single cell work that’s been done here at the Broad and elsewhere over the last seven years.

All along the way, we’ve focused on understanding what’s different in the brains of people who have mental illness. This project is about providing a baseline for that work.

SM: Even in our first conversations about Drop-seq, we had the aspiration that such a technology would someday make it possible to do things like this—to take something that’s incredibly interesting, like human neurobiological variation, that’s not really described at a molecular and cellular level, and to really try to understand it. This is now the chance to do that.

Why is it so important to have a baseline understanding of the range of ‘normal?’

EM: It gets at basic questions about what makes us all different. There are differences that exist at the cellular level, but we don’t really have a sense of what those differences are.

The human genome varies from person to person, but that variation isn’t just random. We suspect the variation of cells in the brain is very similar. There are certain commonly observed variations that you see across people, and those variations evolve in predictable ways across development and aging.

Those are principles that we don’t understand at all, and could lead to key insights into how the brain works.

And I think what’s potentially game-changing is that we’re trying to develop an area of biology that just doesn’t exist. Neuroscience is almost entirely performed on laboratory animals that have no variation.

There are a few notable exceptions to this, but the vast majority of work is on inbred mice that are kept in exactly the same cages over the course of their whole lives. That allows for very disciplined, structured experiments. But it doesn’t give us a sense of the range of normal of what a brain can experience and undergo cellularly.

We’re trying to chart a path towards understanding that variation and how it connects to disease.

SM: Everything in human biology is a range rather than a point measurement. Anytime you get a standard blood test, the results you get show not only the values that you had at that moment, but the range of values that are considered normal. These ranges are wide.

When we talk about human biology, we’re not just talking about one thing—we’re talking about something that’s very dynamic, that changes throughout the day, throughout the lifespan, and that is highly variable even among healthy people.

The human brain is our culture’s favorite monolith. That phrase, “the human brain,” is used as if it were one thing. Relative to a mouse brain, human brains are indeed quite similar to one another.

But the biological variation among human brains is vast and fascinating and includes so many things that we care about. It’s the difference between health and illness and the difference between joy and despair. It’s really important to us to understand the human brain as a dynamic entity.

What tools will you apply to this research?

EM: We’ll use droplet-based RNA-seq and epigenetic analysis. And we’ll also be undertaking spatial analysis. My lab, together with Fei Chen’s lab, has developed a technology called Slide-seq, which allows us to look at gene expression in a two-dimensional section.

Utilizing that technology will be a way for us to start to interpret the variation that we’re seeing, not just looking at the cells themselves, but their positions in space. It’ll be a way of connecting these results to the histology and structure of the tissue in a way that we haven’t been able to before.

What is challenging about this kind of work?

EM: There are the intrinsic challenges associated with building a very large-scale, systematic data set: being methodical, disciplined, organized. Another challenge associated with that is procuring samples that are matched for age and sex and ancestry.

We would like this data set to represent the United States and not just a small subset of it. We’re trying as hard as we can to find samples that reflect that goal.

Scientifically, another huge challenge is going to be the analysis. This is a huge new type of data. We have great people thinking about this with us but, of course, there’s going to be a lot to do to unpack all of this complex data to try to find principles and ideas in the data that will be useful for future work as well.

How do you envision other scientists using this atlas?

EM: It’s kind of our control set for disease. There have been a lot of examples of this in genetics. The UK Biobank and the 1000 Genomes Project were all trying to understand the overall variation of genomes in the population.

That’s what we’re trying to do with this project—just understand the overall variation of brains in the population. That can give you a much deeper and clearer sense of the kinds of analyses to do in disease.

If you know that these certain variations are occurring in people, you can then test, how do those particular variations intersect with disease? Are there particular vulnerabilities?

SM: Human genetics has gotten far ahead of experimental biology in the sense that our ability to discover genes and alleles that affect disease is far greater than our ability to benefit from having found those genes. It’s the great bottleneck in science today.

We’re hopeful that the kinds of data resources and computational approaches that we’ll create will help address the genes-to-biology problem—for example, by seeing how and where the effects of common genetic variations manifest in the brain.

All the brain tissue that we’re going to study in this project is from what are called neurotypical controls. “Normal” is a broad range, and also includes many subclinical states and vulnerabilities, so it’s an opportunity to understand those.

We’ll also apply the scalable lab process and computational approaches that we develop for this project to other efforts studying neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders.

What about this work excites you?

SM: I think human biological variation is such a fundamentally interesting thing. Humans always notice variation among other humans—we’re just built to notice that. But it’s a very different thing to be able to understand biologically what generates that variation. And I think this is a historic opportunity to really start to understand that scientifically.

EM: I’m a psychiatrist. I meet a lot of people in the clinic, and it’s just extraordinary to see the range of behavior and viewpoints and perspectives that can arise in human beings. That has to be encoded somehow in the cells of the brain. We finally have the tools that allow us to start to explore that.

There’s this open sky, big picture kind of opportunity here to learn some fundamental principles about how the brain is organized. And I just can’t think of anything more exciting as a neuroscientist.

This (trance/trans-formation) was mass-scaled around the whole world, since 1666/1776, and esp. since SShlomo SSHItler.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

CIA Murdered JFK & Mary Pinchot Meyer

Janney's mother and Mary were classmates at Vassar College. His father, Wistar Janney and Mary's husband Cord Meyer, whom she divorced in 1957, were both top officials at the CIA.

Janney's mother and Mary were classmates at Vassar College. His father, Wistar Janney and Mary's husband Cord Meyer, whom she divorced in 1957, were both top officials at the CIA. MURDER INCORPORATED

Despite the injunction against CIA involvement in domestic politics, the book reveals that the JFK assassination was only the most prominent of hundreds of US political assassinations. Consider names like RFK, MLK, JFK Jr., Vincent Foster and Senator Paul Wellstone. J. Edgar Hoover was probably murdered.

Janney also suspects that Washington Post publisher Philip Graham was murdered by the CIA who then controlled the Washington Post through his wife Kathleen Graham and Managing Editor Ben Bradlee. This casts into doubt the Post's role in the Watergate Affair. Janney says the 18-minutes missing from the Nixon tapes included his threat to expose the CIA role in the JFK Assassination.

WHO WAS MARY PINCHOT MEYER?

WHO WAS MARY PINCHOT MEYER? Mary Pinchot Meyer is often described disparagingly as Kennedy´s "mistress." In fact, by 1963 she was part of his inner circle and perhaps his greatest influence.

An American blue blood, her father was a two-term governor of Pennsylvania. She was raised in NYC and travelled in the same social circles as JFK. A statuesque beauty, she was high-minded and had no time for the young Kennedy who was a philanderer like his father.

Coming of age during World War Two, she was preoccupied with world peace. She married Cord Meyer, an ex-Marine with an artistic temperament. She shared his commitment to the United Nations as a step toward "world federalism." These young idealists didn't understand the real agenda behind world government.

However Cord couldn't find a job in academia and Mary found herself the wife of a rising star in the CIA. She socialized with CIA families but was not afraid to voice her disapproval of CIA programs. After her divorce, she became a painter and experimented with LSD.

Like Aldous Huxley and Timothy Leary, whom she visited, she believed that psychedelics were necessary for people to break the shell of socialization and experience divine consciousness. She started a group of Washington women dedicated to turning on the powerful men in their lives in order to prevent war.

In 1959, Meyer became reacquainted with Kennedy whose marriage was a sham. Mary turned JFK on to pot and LSD. Kennedy was determined to make peace with Russia and Cuba and wind down the Vietnam War. His Nuclear Test Ban Treaty was passed in the Senate. His emissary was meeting Castro on the day of his assassination.

Mary was privy to the power struggle JFK had waged with the CIA and military industrial complex. Recklessly she voiced her suspicions of James Angleton. She had enough credibility and connections to cause him serious problems.

Mary was privy to the power struggle JFK had waged with the CIA and military industrial complex. Recklessly she voiced her suspicions of James Angleton. She had enough credibility and connections to cause him serious problems.Her murder Oct. 12 1964, two days shy of her 44th birthday, while walking on a canal tow path, was as carefully orchestrated by the CIA as the President's murder. Mary struggled with her assailant and called out for help but was silenced by bullets to the head and heart. Such is the fate suffered by our truest and our best.

Leo Damore was actually able to interview the CIA hit man, now retired, who confessed. This journalistic coup may have cost Damore his life but he had passed the information on to a colleague who gave it to Janney.

Janney's 550-page book is a 25-year labor of love, meticulously researched and measured. Often the author is quite lyrical, giving it a novelistic page-turner quality.

However, Janney does not understand that the CIA ultimately answers to the Masonic Jewish central banking cartel. He refers to an "invisible government" but this is the Illuminati world government. He says James Angleton was a mole but whose mole? The Mossad controlled him for the Illuminati bankers. They weren't going to let an idealistic President impede their agenda which depends on constant war and ever-increasing debt.

The mass media's complicity in the JFK cover up made possible the CIA-Mossad's next outrage, 9-11. It makes possible new false flags almost monthly, hoaxes like Sandy Hook and Boston Marathon. To be successful today, you have to collaborate with the satanic forces destroying America, or at least not challenge them. However, I doubt if ultimately the corrupt ruling class will enjoy the spoils of treason.

Nevertheless, we may find hope in Peter Janney's courageous achievement. Mary's Mosaic is an impassioned defence of freedom based on knowing the truth: ¨The shining beacon of America--a promise unlike any other for humanity-- was being extinguished...[due to] ignorance...I would do whatever it took, pay whatever price was required, to allow this story this small but essential piece of history---to see the light of day." (391)

No matter how depressing, the Truth is always inspiring and so are people like Janney who risk their lives to tell it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7BPijvYec1M

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

The internet has come a long way since Tim Berners-Lee invented the world wide web in 1989. Now, in an era of growing concern over privacy, he believes it’s time for us to reclaim our personal data.

Through their startup Inrupt, Berners-Lee and CEO John Bruce have created the “Solid Pod” — or Personal Online Data Store. It allows people to keep their data in one central place and control which people and applications can access it, rather than having it stored by apps or sites all over the web.

Users can get a Pod from a handful of providers, hosted by web services such as Amazon (AMZN), or run their own server, if they have they the technical know-how. The main attraction to self-hosting is control and privacy, says Berners-Lee.

Not only is user data safe from corporations, and governments, it’s also less likely to be stolen by hackers, Bruce says.

“I think we’ve all come to realize that the value of the web is embodied in the data available on it,” he adds. “In this new world of you looking after your own data, it doesn’t live in big silos that are lucrative targets for attackers.”

Inrupt’s platform is being tested by the UK’s National Health Service and by the government of the Belgian region of Flanders. The latter plans to use Pods to let its citizens choose how to share their personal data.

In October, the BBC introduced an experimental service using Pods for “watch parties,” where multiple friends stream a program at the same time. When the watch party ends, the user can see the data that has been generated, including which program they watched and who else joined, and choose whether to delete or edit the information — or let the BBC use it.

In a blog post, Eleni Sharp, an executive product manager for BBC Research and Development, described it as “a radically different approach to data management.”

Owning your data

Launched in 2017, Inrupt reportedly raised $30 million in December 2021 and Berners-Lee says it will help deliver the next iteration of the web — “Web 3.”

Paul Brody, a blockchain expert for analysts Ernst and Young, believes Web 3 could change the way we use the internet. “You’ll hear people talk about Web 3 and decentralization as being very similar in ideas and goals,” he says.

“Owning your own data and really controlling your own commerce infrastructure is something that Web 3 will enable. It will be ultimately really transformational for users.”

Berners-Lee hopes his platform will give control back to internet users.

“I think the public has been concerned about privacy — the fact that these platforms have a huge amount of data, and they abuse it,” he says. “But I think what they’re missing sometimes is the lack of empowerment. You need to get back to a situation where you have autonomy, you have control of all your data.”

The U.S. Army, not Meta, is building the metaverse

.png)

.png)

!!.png)

,%20they%20Will%20Be%20Exposed%20and%20Punished%20to%20Death%20(everywhere%20in%20the%20world)%20now%2038%20!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment